Well, 2021 did not go as planned. And neither, as you can tell by the fact that I am publishing a post about reads from 2021 when we are just a few hours away from 2023, did 2022. Lots of poor health and funerals and life changes that I won’t bore you with, but also more creative energy than I’ve felt since the pandemic began. Maybe long before.

As a reader, I hit a new personal record of completing 155 books or audiobooks—not including those I DNFed or started in 2021 but only finished in 2022—thereby nearly doubling 2020’s total. Of those 155 entries, here are the ones I would most recommend, and to whom I would most recommend them.

Non-Fiction

The one everyone should read

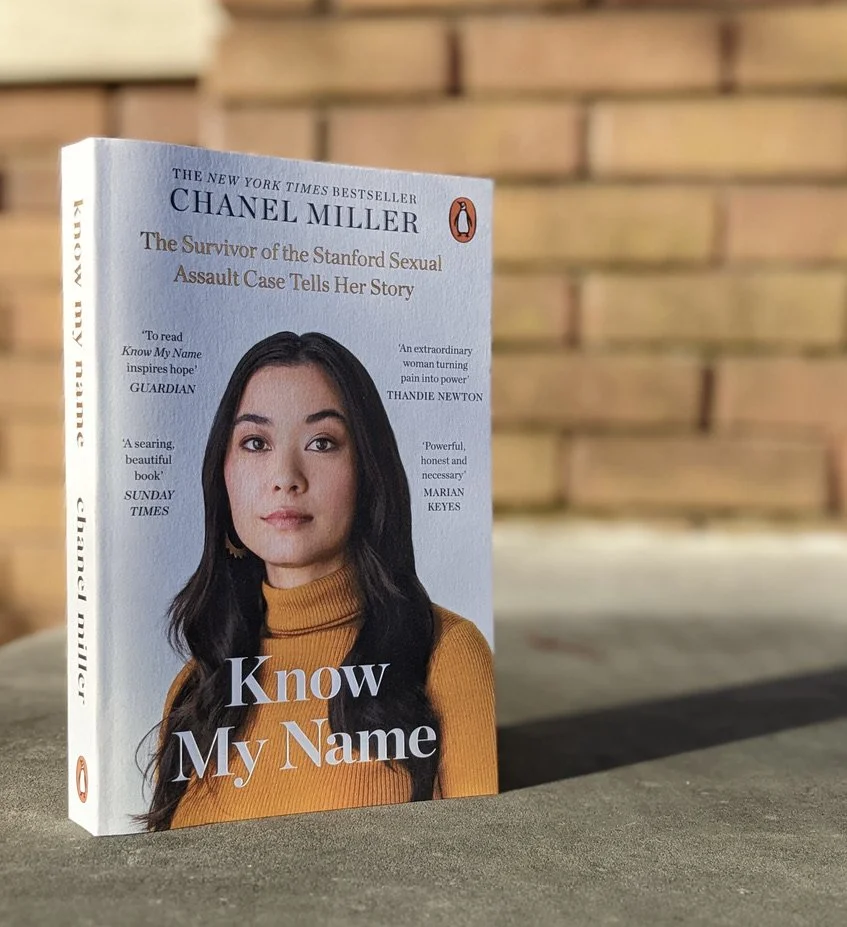

Know My Name, Chanel Miller, 2019

Although the rest of this list will be in no particular order, I am starting with my favorite book of the year. By the time December of 2021 rolled around, I realized that, although I had enjoyed the vast majority of the books I’d read, none of them stood out to me the way the Parable duology and the Testaments had the year before. Then, only a few weeks before 2022, I listened to Know My Name, Chanel Miller’s account of her experiences surrounding and following her rape on Stanford University’s campus. It turned out to be the best book I have come across in a very long time, easily on par with Roxanne Gay’s Hunger in its use of raw, deeply personal experiences to make convincing arguments for social change. It is truly one of the most generous, thoughtful, moving, and impactful books I’ve ever read, while also being one of the most culturally important. It is also the one book on this list I believe literally everyone, especially every American, needs to read.

Better yet, listen to the audiobook where you can hear Miller’s words in her own voice.

the one for those who like their memoirs groundbreaking and a little gothic

In the Dream House, Carmen Maria Machado, 2019

Carmen Maria Machado’s genre-bending horror-memoir is an illuminating exploration of an abusive same-sex relationship and the myriad ways social marginalization can make the abused partner all the more vulnerable. In the Dream House not only presents a perspective rarely seen in any media, but does so in an unusual and effective way: by framing the author’s experiences as a gothic horror story.

The gothic tone and "dream house" framing device, which in other hands might have come off as hokey or exploitative, felt appropriate to both the subject and the author. There is probably a thesis to be written about how Dream House both uses and subverts the long, intwined history of gothic stories and queerness, particularly lesbianism (think Carmilla and Rebecca). However, even those with no knowledge of the gothic will find food for thought here. It easily deserves a spot next to other ground-breaking, socially conscious memoirs like Know My Name (above) and Gay’s Hunger.

the one for all ages

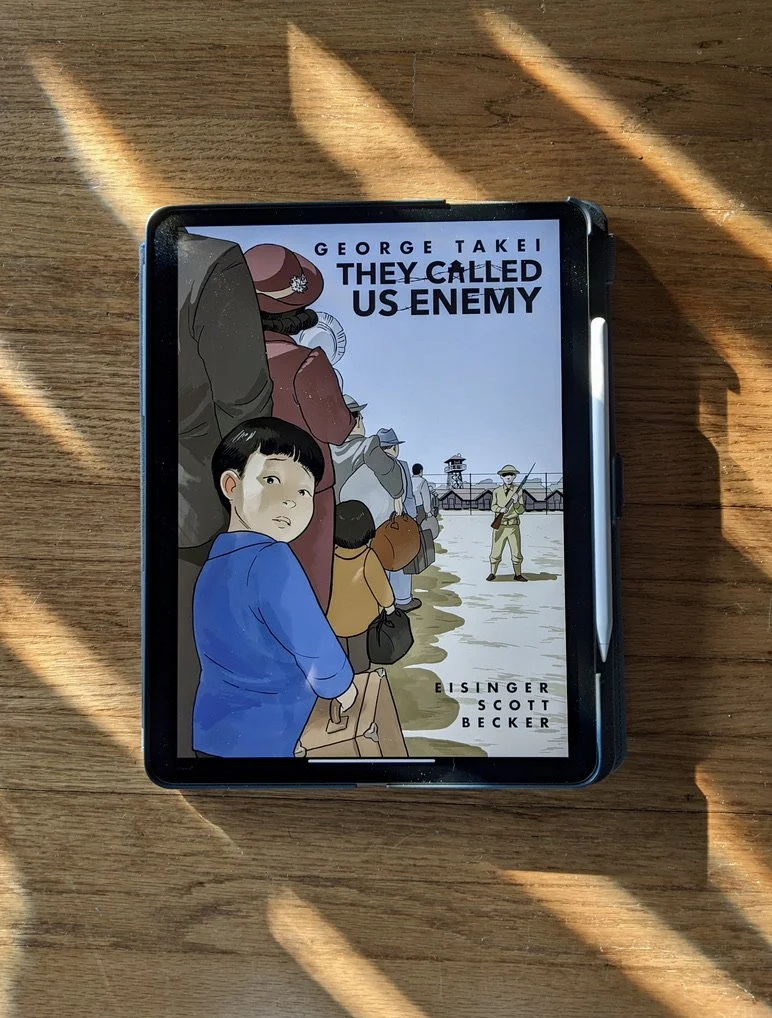

They Called Us Enemy, George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker (illustrator), 2019

This graphic memoir depicts George Takei’s experiences during World War II when the government-supported anti-Japanese sentiment in America caused his family to have their assets frozen, live under curfew, and eventually leave their home in Los Angeles for internment camps in both Arkansas and California.

While not an unknown part of American history, the existence and impact of internment camps has been under-examined, especially outside college-level history classrooms. Takei’s memoir does the important and difficult work of providing a resonant entrance point for this history with a story that is clear without being overly dumbed down, portraying both the ways communities can tear themselves apart in times of trouble and the ways they can pull together.

the one for those wanting their hearts warmed, despite it all

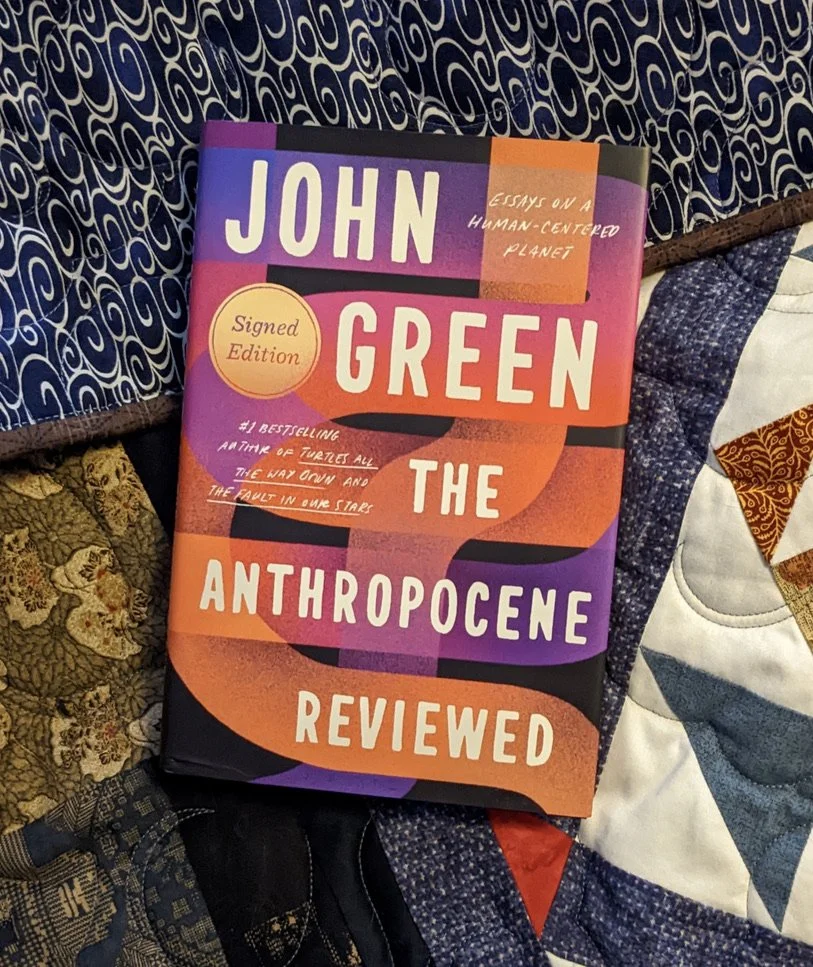

The Anthropocene Reviewed, John Green, 2021

Part memoir, part history, part social think-piece, John Green’s The Anthropocene Reviewed is a collection of “essays on a human-centered planet” based on his podcast of the same name. In each chapter, he weaves together personal experiences with big ideas and broader research to explore a specific, seemingly mundane topic, taking the reader on a journey that ultimately ends with a satirical one through five star rating. Staphylococcus aureas, for instance, gets a sympathetic but firm one star, while the Academic Decathlon receives an enthusiastic four and half stars.

Sometimes funny, always compelling, this is one of the few books that made my eyes well in response to the beauty and generosity of the text. If anything, I worry that the essays might be too neat, too coaxing, and that a second, more critical read could yield a more negative response. Even if that does someday turn out to be the case, I have to believe there will always be value in this gentle hug of a book, and particularly in Green’s persuasively empathetic, hopeful perspective on our current, messy era and even messier species.

This is another book I own a physical copy of but would still recommend first experiencing in audiobook form, to hear the author’s words in his own voice. Since these essays started as a podcast, the audio format feels especially well-suited to the content, and Green is an endearing narrator.

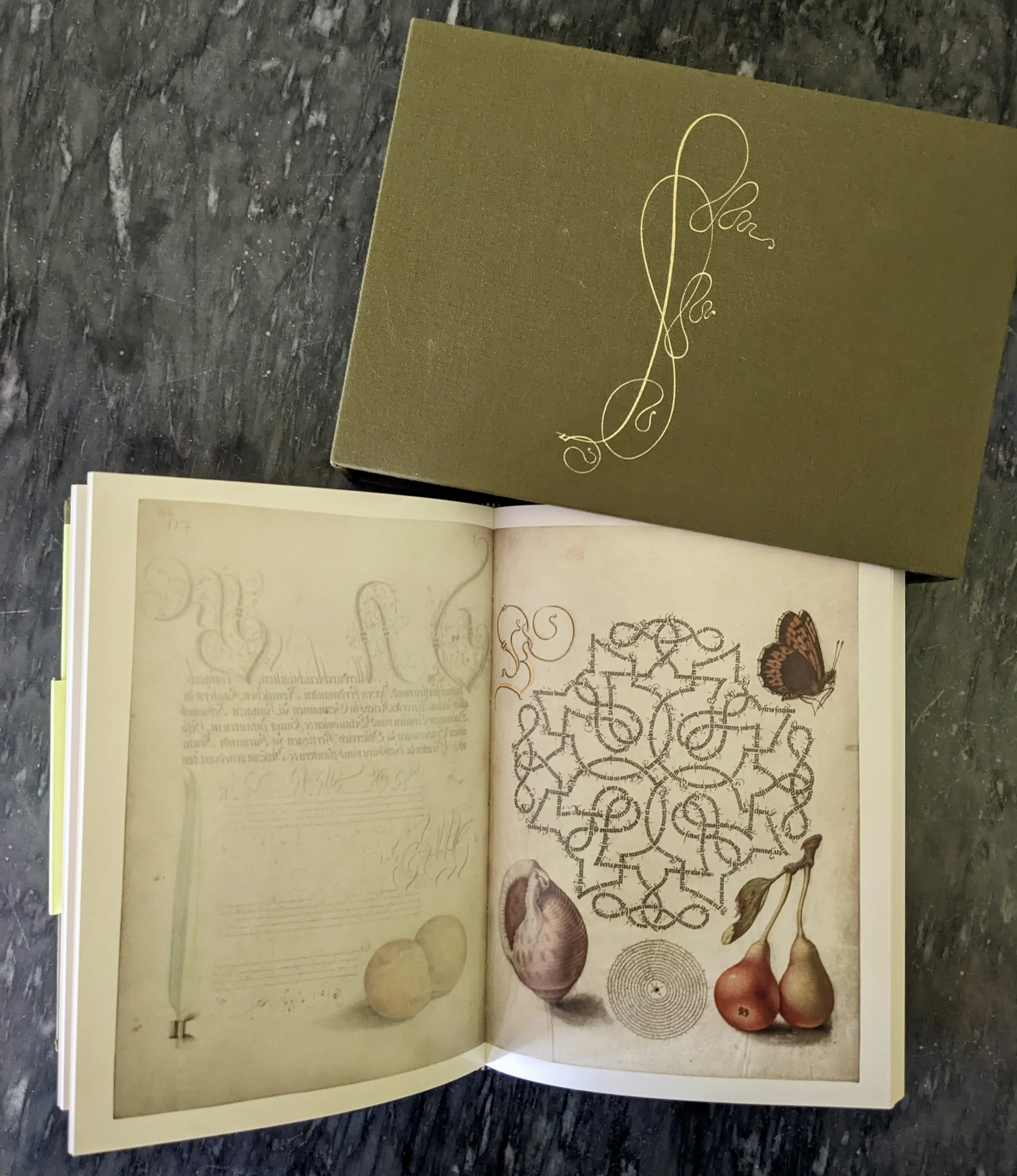

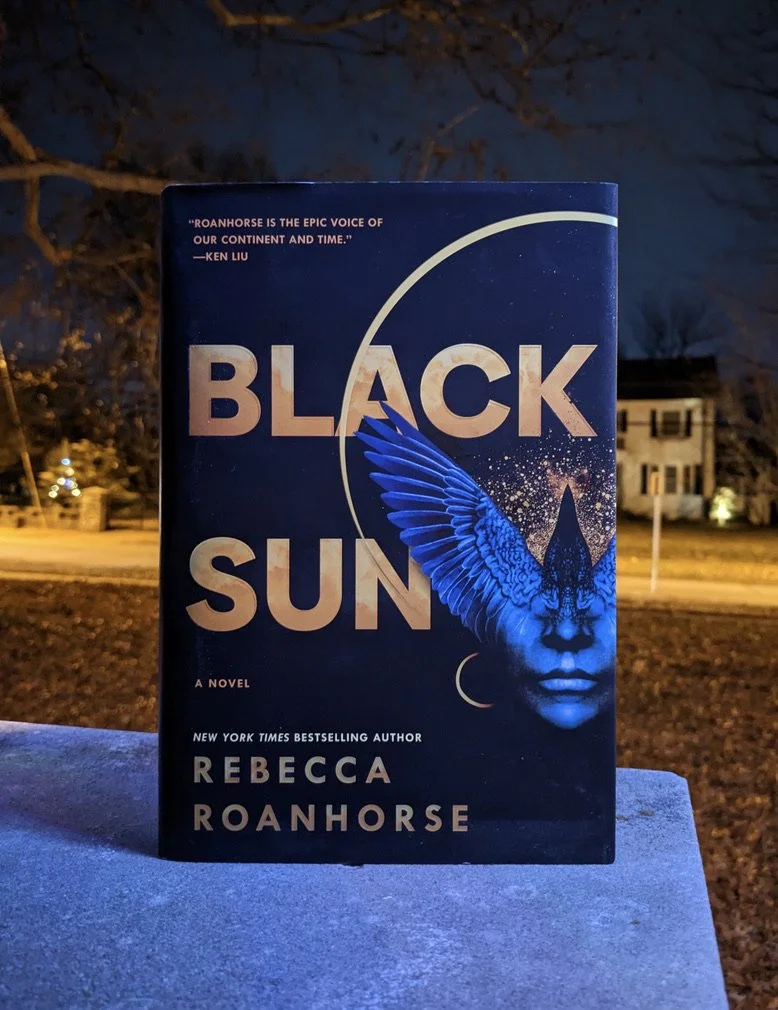

the one for those who want their books about beautiful objects to also be beautiful objects

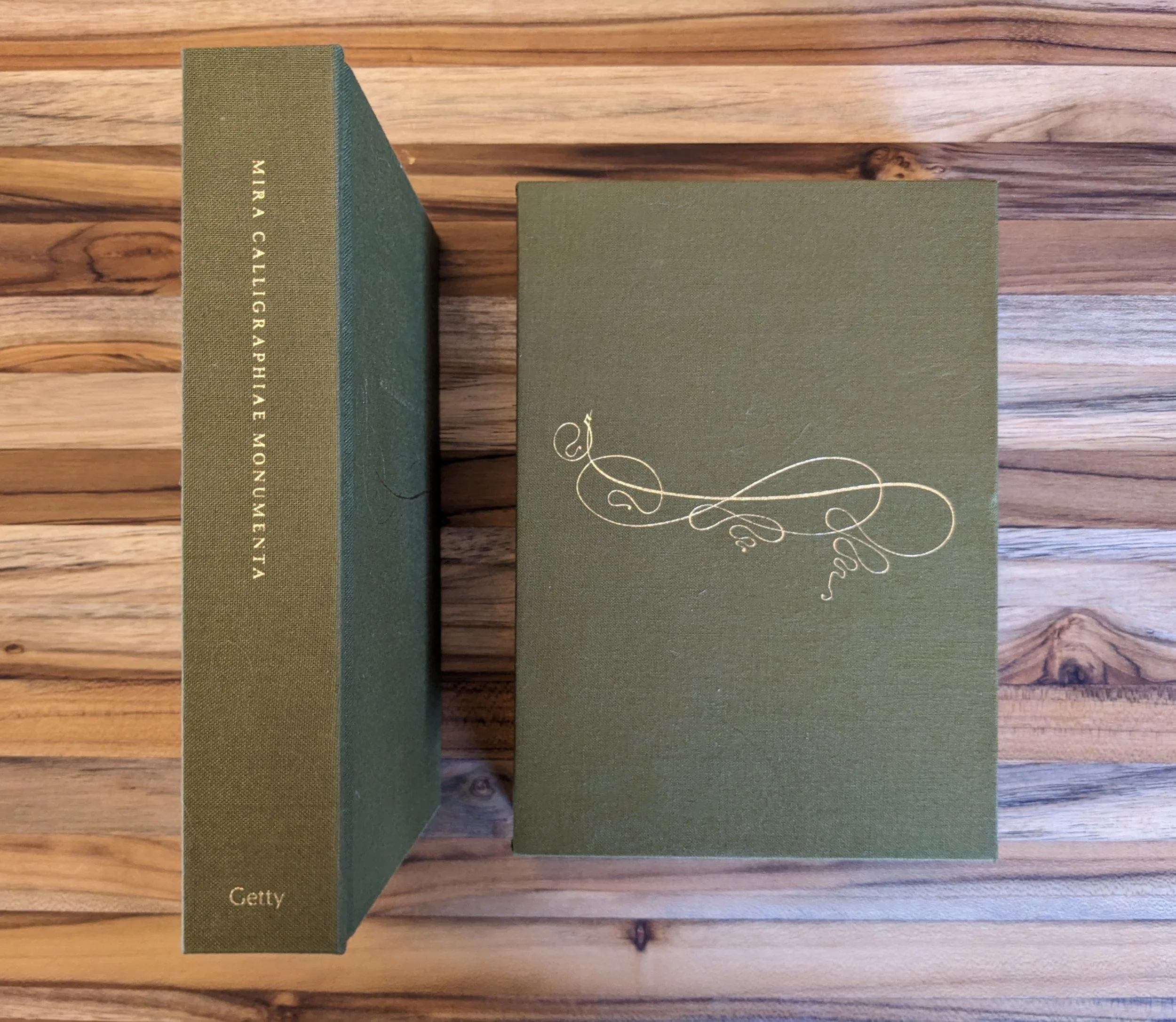

Mira calligraphiae monumenta, Lee Hendrix and Thea Vignau-Wilberg, 1992

Whoa, this little book is gorgeous. Published by the Getty with the exacting standards and high-quality materials I expect from one of the country’s great museums and research institutions, Mira calligraphiae monumenta is a reproduction of Georg Bocskay’s 16th century calligraphic manuscript, illuminated by Joris Hoefnagel. The edition is made all the more fascinating through the informative, accessible essays by Lee Hendrix and Thea Vignau-Wilberg that explore Bocskay and Hoefnagel’s complementary, if competitive, work. Both Bocskay and Hoefnagel used the exceptional quality of their own work to argue for the value, if not superiority, of their particular medium: writing for Bocskay and painting for Hoefnagel. The result is a playful whole, in which two Renaissance masters put forward the best of their ample abilities. As an object, this was easily the best book I held last year.

Fiction

the one that lives up to the hype

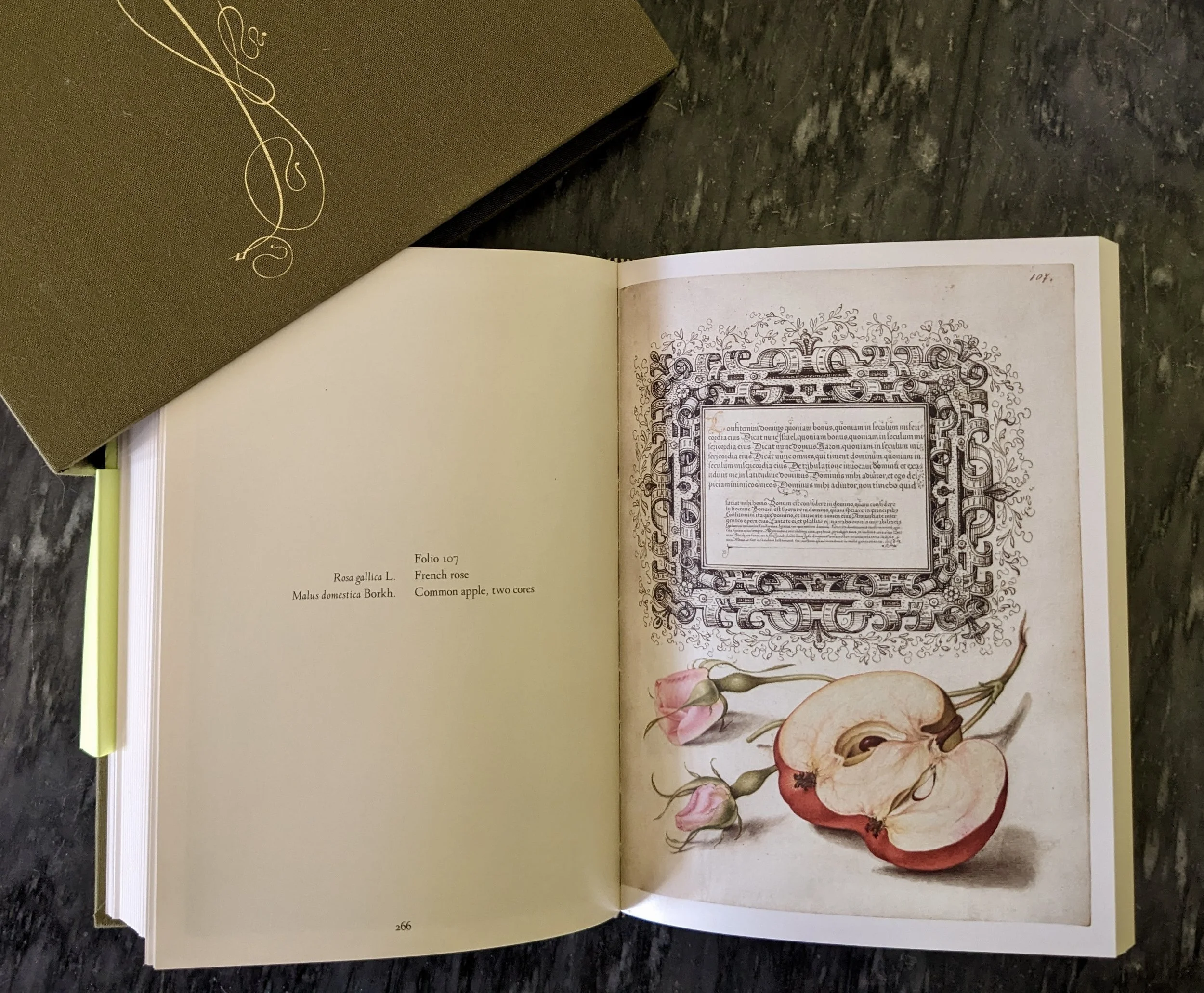

Circe, Madeline Miller, 2018

Madeline Miller is one of those authors who is so popular it actually made me less interested in reading her. And while I am a feminist, I have learned to be suspicious of media advertising itself as such. Still, the number of people who had recommended either Circe or Song of Achilles to me had reached such a crescendo that I finally broke down and listened to Circe on audiobook, narrated by Perdita Weeks. And, damn, sometimes the masses are right.

Circe is a quiet book set in a fantastic, violent, and often cruel patriarchal universe, a retelling of the goddess Circe’s life and the Odyssey from the much maligned female character’s perspective. Miller handles every element of this book beautifully, from the character building and scene-setting, to the clear-yet-lyrical writing style, all of which is underpinned by her obvious mastery of the mythological stories and cultural contexts she is both critiquing and celebrating.

After reading Circe, I picked up Song of Achilles, Miller’s retelling of the Illiad as a doomed romance narrated from the perspective of Achille’s lover, Patroclus. It is an excellent retelling in its own right, deserving of the attention it has already received. However, it is more of a true romance than I was expecting or personally wanted, which is why, of the two, Circe is still the one I prefer.

I also have to say both the American and British hardcover editions of Circe are beautifully designed. It just feels good when the quality of a novel’s content is matched by the efforts of its publisher.

the one that begins with a bang

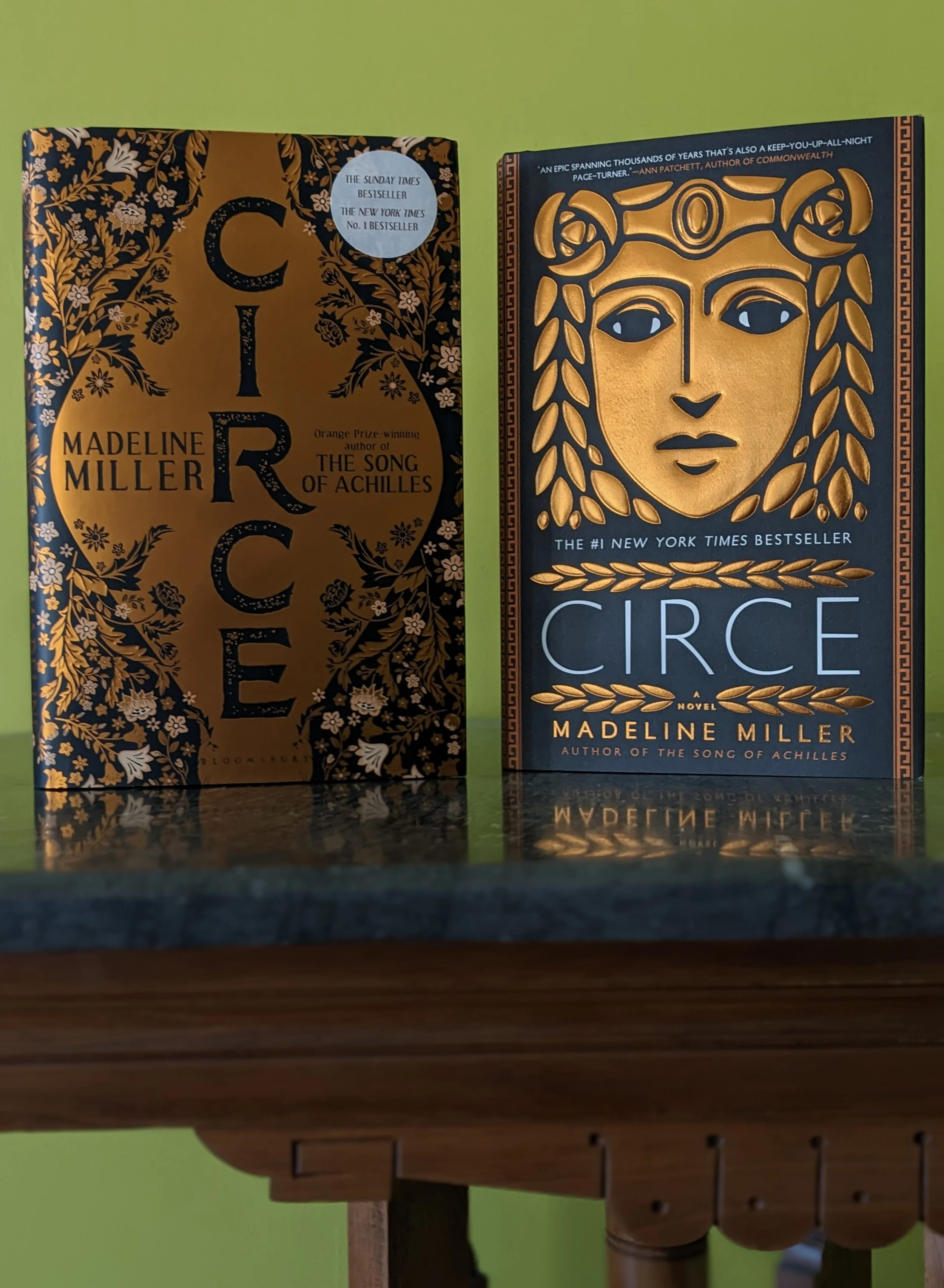

Black Sun, Rebecca Roanhorse, 2020

Similar to my experience with Circe, I was both intrigued by and a little reluctant to read Black Sun, Rebecca Roanhorse’s epic political fantasy set in a world inspired by ancient American cultures—a setting that is particularly dear to my heart. But also like Circe, I was blown away by the book when I finally listened to it.

The story begins with a child being blinded and anointed by his mother while his father, locked outside with members of his clan, begs her to stop. She does not stop, and when she is done, she dives from the cliff outside their home. If that sounds dark, it is. But it’s also one of the most compelling scenes I’ve ever read.

Beyond that impactful, breathless beginning, the book opens up to a vibrant world full of political and personal tensions that is far closer to war than most of its inhabitants realize. Black Sun as a whole is a masterclass in world building, seamlessly encompassing a land populated by diverse, complex, and morally gray people of many skin shades, genders, sexualities, cultures, spiritual beliefs, desires, and loyalties. It deserves to be read by not only fans of speculative fiction but anyone who wants to call themselves a writer.

the one for nerdy feminists, academics, or anyone in stem looking for grounded historical fantasy and a great female protagonist

A Natural History of Dragons: A Memoir by Lady Trent, Marie Brennan, 2013

Oh Lady Trent, where have you been all my life?

A Natural History of Dragons is the first in Marie Brennan’s Memoirs of Lady Trent series. As the series title implies, the books are framed as the memoirs of the now elderly Lady Isabella Trent, a woman who rose to prominence in her fantasy-Victorian world as a naturalist and adventurer while repeatedly risking her life to study dragons. The books are a thoughtful fusion of science fiction—albeit a science fiction that pulls from historical forms of the natural sciences rather than futuristic technologies—and fantasy, building on specific, recognizable ideas and creatures to create unusually solid world building. Even the writing style and character perspectives feel straight out of the nineteenth century, adding an additional level of realism that most historical fiction (fantasy or otherwise) tends to lack.

Likewise, Isabella feels believably part of her pseudo-Victorian era and class, while also embodying that rare main character who is truly, passionately driven by curiosity and a desire for knowledge. In this latter sense, she reminded me a bit of the Biologist from Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation (book, not film), although Lady Trent’s introduction predates VanderMeer’s novel by about a year. The framing of A Natural History as a memoir also means we get a mature Lady Trent’s perspective on her younger self, which adds some important humor and self-awareness to the book.

the one for those who don’t fit

Convenience Store Woman, Murata Sayaka (author) and Ginny Tapley Takemori (translator), 2018 [originally published in Japanese in 2016]

The protagonist of Convenience Store Woman isn’t like most people. She isn’t interested in sex or romance or marriage or wealth. She doesn’t want children and she doesn’t understand the love her sister feels for her own infant. She just wants to be a productive member of society, someone her family won’t constantly try to change or worry about. Her needs are few, and for years she is happy with her job at a convenience store, with its clear rules for what to do and how to interact with other people. But the job is for the young, the kind of thing to tide over unmarried women before they form a family. When the protagonist shows no drive to leave, her satisfaction with her simple life again makes her stand out as disquietingly strange. To appease her ever watchful, normality-obsessed society and keep those around her from trying to fix her life in intolerable ways, she hatches another plan, this one involving a disaffected young man.

Sayaka Murata writes with a unique voice that pulls the reader through this brief novella. The undercurrents of violence and themes of alienation that are taken to more explicit extremes in her novel Earthlings are more subtle here, giving the story a slightly gothic and more restrained feel.

the one with a delightfully twisted sense of humor

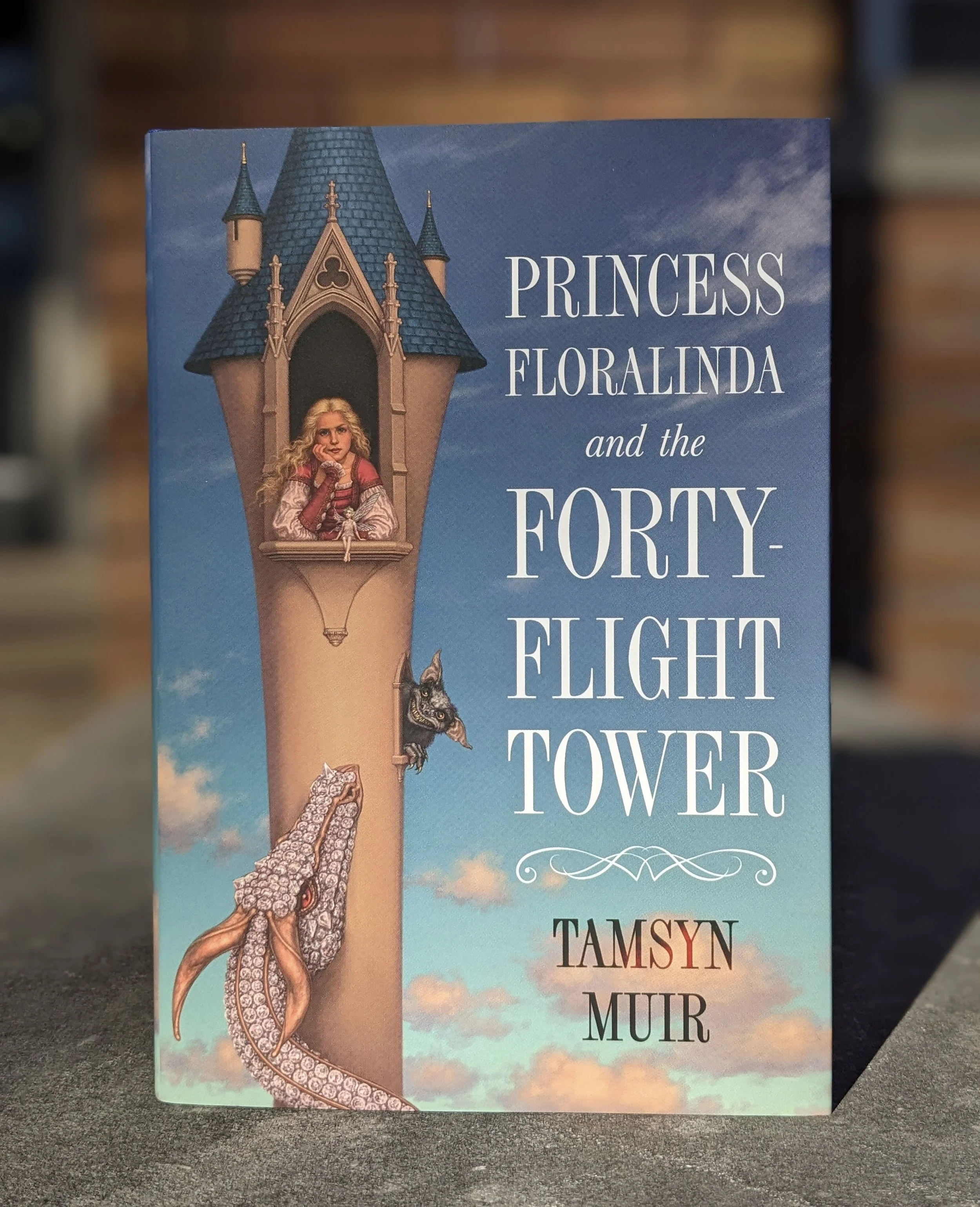

Princess Floralinda and the Forty-Flight Tower, Tamsyn Muir, 2020 [cover illustration by Tristan Elwell]

Tamsyn Muir is currently (and rightly) best known for the darkly funny mysteries following necromantic lesbians in space that make up her Locked Tomb series. However, I have a particular fondness for her standalone novella, Princess Floralinda and the Forty-Flight Tower, which brings her same ruthless humor to fairy tales.

Princess Floralinda is locked in a tower surrounded by the remains of the hapless knights who tried to save (read: win) her. If she’s ever going to get out, she’ll have to become the kind of person capable of saving herself. Each of the floors is populated, video game style, by a deadly challenge, including but not limited to goblins (lots of goblins), a devil-bear, kelpie, and, at the very bottom, a diamond-studded dragon. Needled along by the non-binary fairy who is her only companion, Floralinda tries, fails, and tries some more, all the while getting her hands and petticoats very, very dirty.

The Forty-Flight Tower tells the story of someone forced to change—for better and worse—in order to survive in harrowing circumstances. Yes, it's funny and, yes, it's a send-up of traditional fairy tales, but that humor and conceptual conceit are held up by something both serious and true.

This is also one of those books that I love almost as much for the jacket art—which recalls fantasy paperbacks of the 1980s and ‘90s, particularly those of Robert Asprin and Craig Shaw Gardner—as I do for the content. The cover channels the tone of the story very well and hit all my nostalgia buttons before I even started reading.

The one for those looking for Speculative fiction with sharp, contemporary feminist commentary

The Echo Wife, Sarah Gailey (they/them), 2021

In the Echo Wife, Sarah Gailey uses a near-future, sci-fi premise to create a nuanced, well-paced character study and probing, layered examination of contemporary womanhood. Evelyn Caldwell’s husband is leaving her for Martine. Martine is everything Evelyn is not: traditionally feminine, meek, loving, and happy to be pregnant. She is also Evelyn’s clone. A clone her husband made, secretly, using Evelyn’s groundbreaking research. But now the husband is dead, and Martine needs Evelyn’s help.

Continuing the theme of books I had been reluctant to read but ended up loving, I had put off reading this because it sounded too much like an unpublished short story I wrote years ago that I had hoped to come back to and develop into something better and longer. A part of me hoped I wouldn't like The Echo Wife so that path would still be left open. For better or worse, however, it turned out to be one of the better books I read in 2021. It's so good, I'm not even sorry its existence basically forces me to throw one of my own stories in the garbage. If that's not a strong endorsement for a novel, I don't know what is.

Xe Sands is the perfect narrator for the story, and because of her I highly recommend the audiobook.

The one for those hungry for new perspectives and more indigenous voices

Split Tooth, Tanya Tagaq, 2018

In Split Tooth, Tanya Tagaq—best known as an Inuit throat singer—blends memoir, mythology, and fiction to recount the story of a young pregnant girl growing up during the 1970s in an indigenous community located in the sparsely populated, arctic Nunavut, Canada. The blending of truth and fiction can make the story hard to parse and analyze, but it also offers a singular reading experience and a glimpse into a rarely represented perspective.

The one that merges form with content

Interior Chinatown, Charles Yu, 2020

Interior Chinatown uses a script format and the story of an aspiring Asian American actor to explore, through extended metaphor, the limited roles open to Americans of Asian descent and their often marginalized or ignored place in US culture. It’s heavy stuff handled with a light, almost playful touch, and the result is literary fiction at its most readable and interesting.

the one that reminds us high school was really creepy, actually

My Dark Vanessa, Kate Elizabeth Russell, 2020 [audiobook, read by Grace Gummer, includes an interview between the author and Book Club Girl Podcast hosts Tavia Kowalchuk and Eliza Rosenberry]

I initially had mixed feelings about My Dark Vanessa, a novel about a lonely teenager being groomed by her favorite high school teacher and then, as an adult, coming to terms with the fact that her first sexual relationship was actually abuse. My concerns lay in the places its hyper-realism came into conflict with its occasionally overly tidy storytelling beats, moments that make the book feel a little too much like the well-composed fiction it is. But while I have since forgotten the characters and plots of many stories from last year, this one has stuck with me. In fact, I find myself thinking about it more often than any other entry on this list, partly because a similar open-secret-cum-scandal had broken during my senior year of high school and was being newly revisited around the time of My Dark Vanessa’s release.

The audiobook also includes a helpful extended interview with the author that contextualizes the novel and answers a number of questions about her relationship with the subjects of grooming and teacher-student abuse.

The one for those who want to remember america’s horrific history of slavery but not be crushed by it

The Water Dancer, Ta-Nehisi Coates, 2019

I listened to The Water Dancer, narrated by Joe Morton, at the beginning of 2021, shortly after reading Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad (which was on my best books of 2020 list). Both novels deal with slavery in America through a lightly speculative lens, both feel deeply human and grounded in history, and both are excellent. However, while Whitehead’s take is more difficult and, for me, more memorable, Coates’s is more readable—even beautiful—and the one I would recommend more broadly.