Perhaps it’s because I was born at the end of a Midwestern October, but spooky season—with it’s cool weather, flame-red and yellow trees, darker days, and general sense of unease—has always felt like home. From late September to early November, I gorge on scary movies and books, take long walks at night, eat too much Halloween candy, and generally feel content.

For those in the online reader community, October is also Victober, where participants read stories from the Victorian period (1837–1901) published in Great Britain, Ireland, and the British diaspora.

This year, I’ve been thinking about ways of combining spooky season with Victober, and have come up with a short reading list for anyone wanting to do the same. Some of these are capital-C Classics, so if you haven’t read them already, this October might just be the perfect time to give one or more a try.

Wuthering Heights, 1847, Emily Brontë

The fittingly atmospheric Folio Society edition of Wuthering Heights.

For those who like their October reads atmospheric, psychological, and darkly romantic, Wuthering Heights is the way to go. Set in the West Yorkshire moors, this is a story of class, ambition, passion, cruelty, and revenge, filled with complicated, flawed characters, many of whom die young and tragically. To my mind, Emily Brontë’s novel is also one of the most immersive and engaging books produced during the 19th century. I first read it as a teenager and loved it even then.

“Goblin Market,” 1863, Christina Rossetti

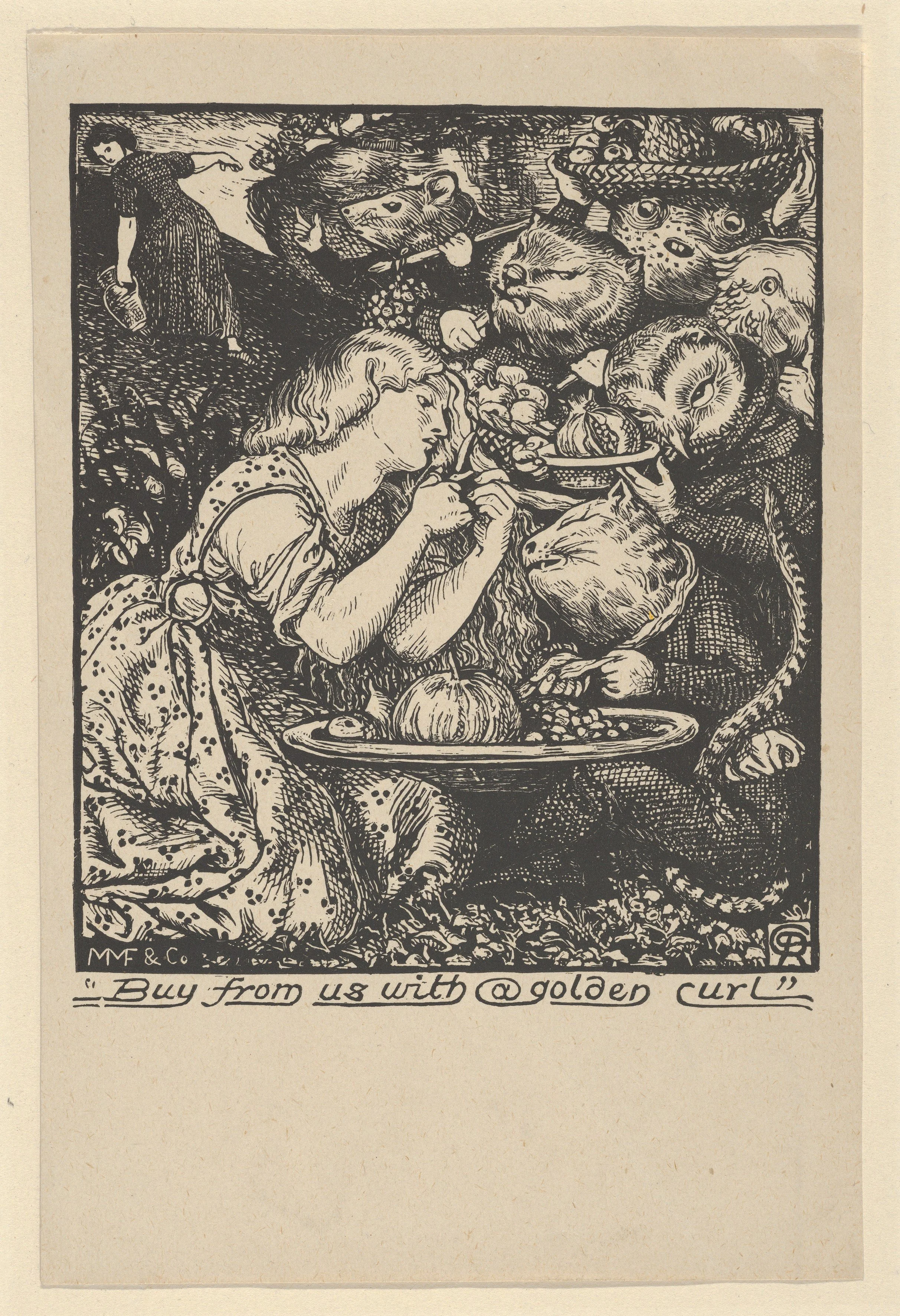

The 1862 frontispiece illustration for Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market and Other Poems. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rossetti’s proto-feminist poem centers themes of dangerous temptations, addiction, and the power of sisterhood, and features highly suggestive, sometimes sapphic, imagery. The poem can be found for free online through multiple sources, including poetryfoundation.org.

Carmilla, 1872, J. Sheridan Le Fanu

Cover of the 2019 Clockwork edition of Carmilla.

Hugely problematic (content warning for anti-lesbian sentiment throughout) but also importantly influential, Le Fanu’s novella following a female vampire and her prey is one of the first published vampire stories, predating Dracula by about 25 years. Le Fanu also wrote a number of shorter gothic tales, often set in his native Ireland, that have been republished in collections like Reminiscences of a Bachelor (2022) and the British Library’s The Gothic Tales of Sheridan Le Fanu (2020).

The Haunted Hotel, 1878, Wilkie Collins

Random House edition of The Haunted Hotel available through Blackwell’s.

If you’re looking for a short-ish read, especially one that combines a murder mystery with a ghost story, put aside Collins’s more popular and oft recommended The Woman in White (1859) and pick up his Haunted Hotel. Set between Britain, Ireland, and Venice, The Haunted Hotel tells the story of one mysterious disappearance, one apparently natural death, and the disturbing visions and emanations that affect only certain guests of a Venetian palazzo-turned-hotel. The novel feels both very Victorian and genuinely creepy, with expected levels of melodrama and a dollop of romance.

The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1890, Oscar Wilde

Penguin Random House Vintage Classics edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray

In Oscar Wilde’s story of moral degradation, a once innocent young man allows himself to fall ever deeper into corruption, destroying those who once loved him as he lives on, as youthful and beautiful as the day his portrait was painted. Meanwhile, the portrait grows ever uglier, revealing not just his age but also the outward signs of his cruelty, debauchery, and hard living. The idea of physical beauty equalling moral beauty is very Victorian, but also lives on today more than most of us would like to admit. The Picture of Dorian Gray is thus not only interesting as a document of its time but also still has the power to resonate with contemporary audiences.

To Let, 1893 and “Number Ninety” and Other Ghost Stories, B.M. Croker

A collection of B.M. Croker’s ghost stories, available on Amazon.com.

The cover of an 1893 edition of To Let, as pictured on Tartaruspress.com.

Irish author Bithia Mary Croker wrote many ghost stories in the 19th century, including a number set in British-controlled Asia. Married to an officer in the Royal Scots Fusiliers and the Royal Munster Fusiliers, Croker lived in India and Burma from 1877 until 1892. Her ghost stories “To Let” and “The Dâk Bungalow at Dakor” both address the unwanted British presence in colonial India, albeit from the perspective of a British woman.

The collection published as To Let, including the titular story, is available for free through Project Gutenberg or for purchase on Amazon through Black Heath Editions. “Number Ninety” and Other Ghost Stories is available for purchase through Swan River Press. I plan to read the Project Gutenberg version for the first time this month, so can not offer content warnings based on my own experience with the work; however, according to other people’s reviews, the stories are imbued with an outdated colonial perspective.

For more information on B.M. Croker, see Melissa Edmundson’s article, “Bithia Mary Croker and the Ghosts of India,” published in the Winter 2010 edition of CEA Critic and available through JStor.

Dracula, 1897, Bram Stoker

A Penguin Random House hardback edition of Dracula.

What can I say? As one of the most famous and influential horror novels ever, Dracula is probably the most obvious pick on this list. Much in it is still shocking and brutal (ie, stalking, drinking blood, eating babies, staking and beheading a beloved character, etc.) and seemed even more so at the time of its original publication.

The Turn of the Screw, 1898, Henry James

Penguin Clothbound Classics edition of The Turn of the Screw and Other Ghost Stories.

A classic of gothic horror, Henry James’s novella The Turn of the Screw follows a young governess as she struggles to save her charges from dark forces that live either on the estate, in the children, or in her head.

Both the collections The Turn of the Screw and Other Ghost Stories (Penguin Random House) and Ghost Stories of Henry James (Wordworth Editions) include the novella as well as additional short stories that (mostly) fall within the Victorian period.

Bonus, not-quite-Victober read:

A Penguin Random House hardback edition of Frankenstein.

Mary Shelley’s originally published text of Frankenstein dates to 1818 and the revised version is from 1831, both preceding Queen Victoria’s reign. But if you just want a Halloween-appropriate classic, you could do worse than this tale of a 19th century incel and his maker.